On paper, we are a free world, a world where we have the right to choose our beliefs, do what we love, and exist how we want.

But is this really true?

A quick look at social media or the news will bring forth the stories of bigotry and discrimination. The world which welcomed mass globalisation at the beginning of 21st century has turned 180 degrees and is now moving towards more nationalistic and totalitarian rule.

In 2020, where the whole world has come to a grinding halt with the pandemic, unlike what Hugh Grant led us to believe in love actually, the messages pouring through are not ‘love’. The abuse of Dalit women in India or the more recent farmer protests, the frequent killings of African Americans in the USA, moving of Hungary from democracy to a hybrid regime, with the prime minister holding more power than the constitution. The ban of independent newspapers in Iran and few other countries allegedly prevent the spread of the Corona Virus. Complete lockdown preventing access to basic needs for lower strata of society in certain African countries. The list is endless.

Society at large is on the edge, obsessively studying the news and graduating from the ‘whats app university,’ or the ‘Facebook university’. Originally a tool to connect and reacquaint with loved ones, off late they’re being used to propagate hatred, twisted facts, and misinformation. The ‘my way or the high way’ brigade is on the prowl and they will not rest till they either convince everyone or persevere to numb citizens again and again till they cannot differentiate the right from propaganda. Trolling and social media attacks are regular trending hashtags now.

So, coming back to my original question, in a supposedly free world, are we really free? Or is it the luxury of privileged few and forbidden for others?

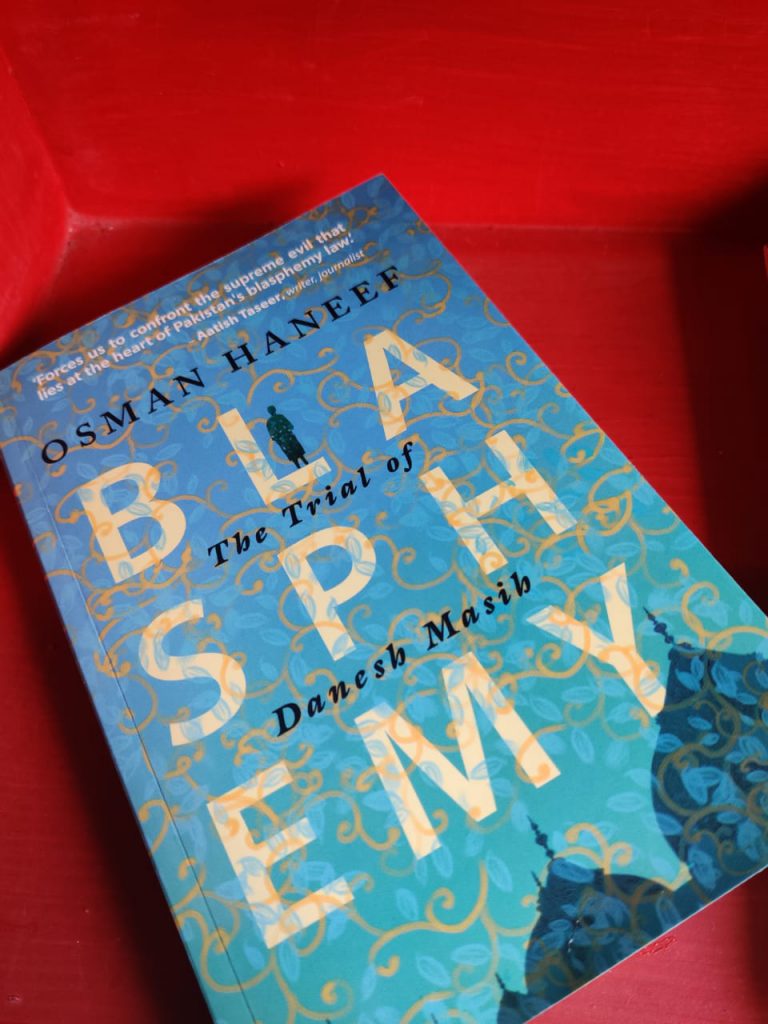

Chatting with Osman Haneef on the eve of the launch of the print version of his maiden book Blasphemy – The Trial of Danesh Masih. I posed the same question to him. Here are few excerpts from the discussion

Osman, what according to you makes something forbidden? Who decides what is forbidden?

Traditionally, when we think about who decides what is forbidden, we think of governments or powerful non-state groups. History is replete with examples of such censorship, for example Galileo’s censorship by the Catholic Church. More recent examples include Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code (banned in several countries) or even Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.

Essentially anyone with the power to inflict harm on the transgressor who produces a forbidden text, has the power to determine what is or is not forbidden.

However, if we dig a bit deeper, we realize that it isn’t these groups that decide but we, the people, who decide what is forbidden and what is permissible. No group or state can stand up to the will of the majority of the people indefinitely. And for that reason, it is important for us to lend our voice to powerful ideas of justice and equality. Ultimately, we all decide what is forbidden.

In 2018, BBC reported that Facebook had a massive role to play for the supposed anti-terrorism measures but actual ethnic cleansing that happened in Myanmar, a Whatsapp forward has taken more than 17 lives in India. Do you think Social Media has been key in this decision?

The pervasiveness of social media has made it much easier for groups to organize and for ideas to spread at an unprecedented pace in human history. And, the examples you presented do suggest that social media is being used to spread intolerance and hate. But extremism and radical ideologies predate the internet, and social media, like many other technological innovations is simply a tool. It can just as easily be a tool to mobilize people for positive social action as it can be used as a tool for violence, radicalization, and spreading misinformation. Ultimately, our use and regulation of social media is a question that we will all have to answer for ourselves.

The 2020 report of United States Commission on International Religious Freedom reports an increase in Religious persecutions world-wide. We’ve seen evidence in Rohingya, bombings of churches in Srilanka to count a few. How do you then account for this extremism?

The academic literature on the root causes of extremism and religious intolerance is vast, and I don’t want to be reductive. But, to me, one of the most compelling theories relate how periods of economic growth followed by periods of stagnation foment violence and extremist behaviour. Why? As people’s outcomes fail to match the reality of the world, they find themselves in, they become frustrated. Opportunistic political actors channel this anger towards a scapegoat, such as a religious or ethnic minority group. Demagogues use this dissatisfaction and frustration to further their own political interests. In what is likely to be a global recession, I fear there will be a rise in religious intolerance and violence.

Let’s talk about the Blasphemy law which is almost at the helm of this growing religious intolerance. In fact according to the Pew Research Centre, about a quarter of the world’s countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014. What encouraged you to pick this as a topic?

I wrote the novel as a “discovery” writer. That is, I wrote the first draft without a strong sense of the narrative arc or central conflict. But as I wrote, my mind kept coming back to a blasphemy case from the 1990s. In the case, an illiterate teenage boy, Salamat Masih, was accused of writing blasphemous statements on the wall of a mosque in a village in the Punjab. There was no physical evidence, and the judge was never told what was said because to repeat the statement would have been blasphemous. Eventually, the conviction was overturned, and Masih fled to Germany. However, the injustice of an obviously innocent young boy wrongfully convicted in this Kafkaesque court proceeding in Pakistan stayed with me.

How was the experience of writing a book of such underlying malaise in the society and yet doing it in a way that did not hurt sentiments?

I did not set out to write a polemic and, though the book is critical of the blasphemy laws, and takes place against the backdrop of a blasphemy trial, it is a book about fully formed characters. I wanted to avoid caricatures, such as villains with twirling moustaches. For instance, with Pir Piya who is the primary antagonist in the novel and a deplorable figure — my aim was to have readers understand him even if they weren’t sympathetic towards him.

Did at any point you feel unsure or worried that it might affect your life, as in risking it?

Even though my novel is not blasphemous, people don’t need a good reason to vilify and target you.

And many people understood the risk. It made it challenging when I was looking for agents and publishers, especially in the West. A prominent British literary agent told me that after Rushdie, no one wanted to touch a book on blasphemy. I explained that my book wasn’t blasphemous but the agent pointed out that the people who would object probably wouldn’t necessarily read the novel to find out. Eventually I did find an agent, Sherna Khambatta, and a publisher, Dipankar at Readomania, who understood what I was trying to do, and they helped bring this novel into the world.

But, to more directly answer your question, yes, I was worried (and still am). You can never feel completely secure when writing about blasphemy. Salman Taseer, the Governor of Punjab was murdered by his own bodyguard, for taking a very moderate and reasonable position towards the law.

These days, messages of tolerance and inclusivity are often met with violence and threats. But if those of us with the ability to write about these topics, don’t out of fear, then we cede the debate to the most extreme elements of society. Those of us with the power to do so, need to speak for those who don’t. If we don’t confront them while we can, it will soon be too late.

Blasphemy (the book) is not only about the trial, running through it, are threads of beautiful storylines. How easy/ difficult was it to create subplots in the book, each giving a further layer to the characters?

It is often said that the key to good writing is rewriting. And that was the key to weaving the stories together. It was many hours of rewriting, and cutting, leaving only what worked to tell a coherent interlocking story.

Talking about the characters, it boasts of some powerful relationships, connections and contrasts – Sikander- Fazal, Danesh – Pir piya, how easy was it to weave these without diluting the core topic?

My novel is chiefly about the characters and their relationships. I know I talk about the blasphemy trial but that is only interesting in how it brings the characters together and forces them to confront each other and their past. I sincerely believe that if a writer focuses on characters and their relationships, the rest takes care of itself.

In an earlier interview with Readomania, you mentioned writing about Pir Piya was the most difficult, can you tell us a bit more?

The most difficult characters to write in Blasphemy were those who the most far removed from my own perspective and point of view. These characters were probably the antagonists because I was forced to unpack the motivations for their deplorable actions. For instance, for Pir Piya, a radical religious preacher in the novel, I read extremist literature and watched videos of religious extremists to understand the way that they justified their positions. I combined that with what I knew from all the research on radicalization and extremism and the people I had met to develop the underlying psychology of the character. I then tried to imagine how a character with this fabricated background, and way of engaging the world, would think and respond in different scenarios. And then I kept editing it and changing it until it felt true.

Who was the easiest to write? Rather who is your favourite character?

The easiest characters to write were probably Sanah and Sikander because their views of the world are probably closest to my own (though we definitely have our differences). Still, it didn’t require as much of an imaginative leap as Pir Piya. But my favourite character to write was Ahbey. It let me enter a childlike place of wonder and excitement that I found compelling.

They say the first book is autobiographical to a certain extent, in fact we saw Sikander sharing your love for drawing comics? Does blasphemy have a sprinkling of your life?

I am sorry to disappoint everyone but it is completely fictional. But to clarify, I may borrow experiences or stories people have told me as a starting off point. But then, I exaggerate them and change so much that the characters and stories become unrecognizable. In order for fiction to seem true, it often needs some basis in fact but, in the end, it is fiction.

Where else do you get inspiration for your writing? Do you have a writing schedule?

I could get inspiration from anything: personal experiences, the stories and myths people share, people I meet, books, movies, and television. I mine everything. That’s why you have to be on your best behaviour when you are with a novelist, you don’t want your name to end on a terrible character who sounds a bit too familiar. In fact, my brother said that he had never been more relieved to not see a character based on him in a novel. So clearly, he was nice to me.

I used to write on weekends because my job was all consuming during the week or would leave me exhausted. However, these days, I have been struggling to write at all. It has been difficult during the pandemic but I hope to get back to it. And it is not because I don’t feel like it…I will say the key to writing, which I feel most beginning writers struggle with, is that they wait for the muse. That is getting the writing process backward. You don’t write when the muse comes. You write so that the muse comes.

Lastly, with the world in the state, it is in, where do you head from here?

I don’t have grand visions for the world. But I know that many people are struggling — with lack of work, mental health issues, family problems, and so much more.

I hope that in this difficult time we show a bit more kindness towards each other, and check-in and reach out to friends and neighbours who we haven’t spoken to in some time. It is during these, the most challenging of times when our friends and loved ones need us most. And the world could always use a little more kindness.

Osman Haneef was born in Pakistan and, as the child of a diplomat, grew up in different cities in Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East. He studied creative writing at Yale, Stanford, Colby, Curtis Brown Creative, and the Faber Academy. He won the Frank Allen Bullock Prize for creative writing at the University of Oxford. In a former life he worked as tech entrepreneur, a strategy consultant, and a diplomatic advisor. He was selected as a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum in 2017. He lives with his family between the UK and Pakistan. The print version of his maiden book – Blasphemy – The Trial of Danesh Masih is now available on Amazon.